The city, or rather, the town we’ll focus on today is not one you will see mentioned on the “Must-see” list of TripAdvisor, or even on some alternative travelling guru blog. Twistringen, self-proclaimed “Perle in Niedersachsen” (Pearl in Lower Saxony, basically the German equivalent of the Jewel in the British Empire’s Crown, if you have the right amount of self-derision), is a town of 10 000 inhabitants in northwestern Germany, 50 km away from the city of Bremen. While its history stretches back far enough to make any American tourist let out a gasp of “Wow, that’s sooooo much older than our Constitution!”, most of these centuries until today have been marked by the seasonal rhythm of ploughing, soughing, growing and harvesting, year in, year out.

As repetitive as these agricultural cycles might be, peoples’ lives in the area have undergone profound changes with times. And yes, you saw me coming: those changes are inevitably linked to the energy sources that were driving their everyday lives. In the mere 25 years of my humble existence, I was able to observe some of these changes myself as I came back almost every year to my grandparents place. That’s why I wanted to take you on a little trip through time, inspired by many family anecdotes (possibly embellished by the amount of Schnapps imbibed at the time of telling), to explore how energy has shaped peoples’ life in the region.

Twistringen originally lies in a marshy area. Peat, which is formed by anoxic (fancy word to say without oxygen) decomposition of organic matter under the water surface, was therefore commonly found. Peat being the first step in the natural creation of coal, it also has some valuable properties as a combustible, a.k.a. heating fuel. The heat which can be extracted from a combustible is generally referred to as heating value (very creative, I know). Peat has a heating value of around 10-15 MJ/kg, similar to dried wood, while the purest type of coal has a heating value of around 30 MJ/kg, and natural gas lies above 50 MJ/kg (if you have pyromaniac tendencies, you can find a more complete list here. And before any of you nerds make a comment, I’m using lower heating value here). To put it short, you have to dig up a lot more peat out of the ground compared to coal or natural gas to keep you warm at winter. And with a renewal rate of 1mm per year, it is hardly something you can consider a renewable source of energy. The poem “Der Knabe im Moor” gives us a little glimpse of what life in the marshes was like, and suggests that few looked back with nostalgia to these “good ol’ days”.

As King Coal rapidly became enthroned in the 19th century as the driver of Germany’s rapid industrialisation, coal also eventually made it into private homes as a heating fuel, while wood was still used for cooking. As the region around Twistringen didn’t have any coal resources itself, it had to be imported from the booming Ruhr area to the South. Coal was to play a key role as a heating fuel until at least after the Second World War. While WWII History often focuses on the atrocities committed at the frontline during this dark chapter of German history, life was also giving its fare share of lemons to 10-year old Peter (hi Opa!) and his comrades in the war-struck hinterland. Coal resources for heating were becoming scarce, as they were entirely dedicated to the war effort, such as fueling the high-heat furnaces for steel production. Coal was needed to obtain coke (completely legal stuff, I swear!), allowing to reach the 1600 °C temperature required for steel production. The coke scraps from the production process were a valuable substitute as an energy source to heat up peoples’ houses. And so Peter and his little comrades literally ended up being heated by bullet and submarine production waste. Pretty efficient use of energy, if you ask me…Shame it had to be at the service of such an evil cause.

With the war over and Germany forced to pay its war tributes without a penny left in the treasury, coal became a currency to pay the Brits, who’s economy was just as much on its knees. Wagons loaded with the precious fuel were transported by train from the Ruhr region to the German harbours on the North Sea before being shipped off to her Majesty’s subjects. As these coal-laden wagons passed through Twistringen at night on their way to the harbour, “Kohlenklauer” (Coal thieves) would jump on the wagons, fill up their bags with coal and jump off as quickly as they came, playing Robin Hood against their own Motherland to secure a warm soup for the family.

While the years after the war were rough (I’ll skip my granddads anecdotes of canoeing on the river in cut-out bomb shells), West Germany quickly got back on its feet again. The coal heaters soon got replaced by cleaner, safer, more efficient and transportable natural gas. The problem is… there ain’t much gas in Germany. It was time to make friends. The widespread adoption of gas came with the discovery of vast natural gas resources in the North Sea in the 70s, in the territorial waters of neighbouring countries. But while the Netherlands and Norway became important gas providers (21% and 33% respectively to this day), Germany had to look further East to quench its thirst. Gas relations with Russia started in the politically tense context of the Cold War, and remain a thorny issue to this day. Indeed, Russia represents the large majority of the remaining gas imports, and gas pipelines such as NordStream I and II have been laid to connect the two countries directly, as supplies from the North Sea countries are expected to decrease. In the little town of Rehden, just south of Twistringen, own of the largest gas storage facilities is being connected to the NorthStream pipelines, to have gas reserves for rougher days and avoid the price (and emotional) rollercoasters which many countries accross Europe have experienced over the past year.

Now you’ll tell me, that’s not very green, all that. Point given. That’s where Germany’s Energiewende comes in, boosted by the nuclear accident of Fukushima in 2011, which increased the public support for renewable energies. Solar panels popped up like mushrooms on farmers’ barns and peoples’ homes, almost giving the impression of being in a sun-blessed region of Europe. My work experience as a solar panel roof installer the next year in freezing February reminded me how much impressions can be far from reality. But regardless of 4pm-darkness during winter nights, citizens were happily covering every available surface they had with photovoltaics. The reason was simple: like a baby learning to walk, the solar industry was heavily supported by the state through subsidies, which also benefited German solar panel producers, which at the time were leading pioneers in the nascent industry.

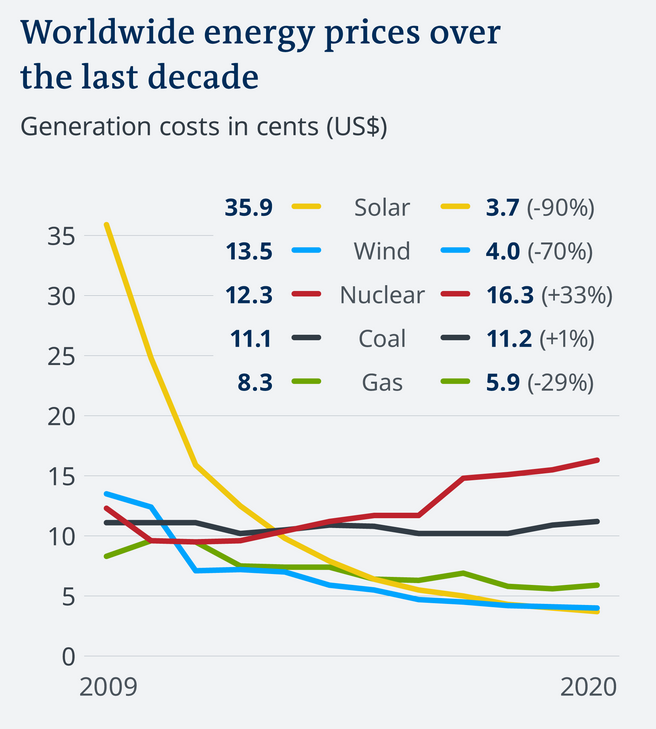

All this was 10 years ago. I will let you admire below how cheap the stuff has become since:

(graph taken from Deutsche Welle)

However, despite this price drop, Germany’s (and Twistringen’s) solar panel installation rate literally plunged after 2012: new solar panel competitors from abroad, particularly China, left home manufacturers bankrupt, while state remuneration mechanisms simultaneously started to fade away. Damn, why does hitting puberty always have to be so hard? Luckily, predictions backed by encouraging numbers in recent years promise a new upswing of the industry in the years to come.

While Twistringen’s flirt with the sun is a perfect example of the “every little helps” approach of our energy transition, the real MVP of such flatlands by the North Sea remains wind. Today, wind energy represents 38% of the regions’ electricity production (remember, electricity, not energy!). Driving around the area, I often try to count how many turbines I can spot around me…It usually ends up in the 70s to 80s. At a rated power of around 2MW for the older models, you have 150MW blowing around you at all times. That’s as much power as 1,500,000 TVs on at the same time, or 500,000 Tour de France cyclists pedaling simultaneously, or 150,000 toasters on (jeez, that’s a lot of cyclists for a piece of burned bread 😉 ). Undeniably, these white slender towers have transformed the scenery. As kids in the car on our way to our grandparents, me and my siblings always tried to be the first to spot the church tower of Twistringen. Nowadays, that game would have lost a fair share of its fun, the church tower having received a bit of company in the Twistringen skyline, with all the wind turbines around it. But far from being a reason to complain, the people I’ve spoken to seemed quite proud of this change. For once, they were drivers of this change, a change which seemed to benefit both them through new jobs and revenue opportunities, and society as a whole by responding to climate targets.

Nowadays, Germany’s Energiewende relying on a 100% renewable society is challenged, and rightly so. The country is struggling to reach its climate targets, and large spans of the economy remain highly dependent on fossil fuels. The road to cover by renewables in the next few years appears daunting at best, with a fair share of sleepless nights to be expected for the incoming government. But when planning for the future, a look back at what has (and hasn’t) been achieved so far is essential to move ahead. And this is where the beautiful but frustrating nature of renewable energies becomes apparent: there is no one-size-fits-all solution, unlike what we’ve been used to with our economy based on standardised mass-production. Every case, every solution, must be built around the environment, the people and their history which has brought them this far. So cheers to a complex world, full of unique and challenging situations. Und ein Hoch auf Twistringen!

I enjoyed reading your text ! Lovely writing about an adapting village.

Wohl gesprochen, Nico.

Niedersachsens Perles late history nicely decomposed