While listening to scientists has been pretty trendy in the last few months (what a revolutionising idea!), the outcry “Listen to the science!” had already been going on for months before, spearheaded by the one and only Greta Thunberg. Except that at that time it was concerning climate change, environmental pollution, threatening of biodiversity, resource depletion – the list of anxiogenic phenomena goes on.

Since then, a lot of parallels have been drawn between how the COVID-19 crisis is being handled and how we have been dealing with the environmental issue so far. And when we see the dramatic societal changes that have happened within just a few days, driven by necessity, the pretty unanimous verdict regarding our progress on sustainability seems to be: we can do better. Much better.

But then how come we don’t? It’s not like sustainability issues (sorry, I keep using this word to refer to the list of catastrophes mentioned in the first paragraph, for a lack of other all-ecompassing word – other suggestions always welcome) are constantly being mentioned in newspapers and public debates. Only 80% of the time. It’s fair to say that compared to only ten years ago, discussions have made incredible progress regarding sustainability. But the problem is just that. They mostly seem to remain fruitless discussions, with a tendency to drift off into arguments, incoherent shouting, and ruined dinner partys (only slightly exagerating here).

While all future scenario studies indicate the urgency of steeper and steeper emission reductions to meet sooner and sooner carbon neutrality deadlines, the share of fossil fuels in the world’s total energy consumption has stubbornly remained the same for the past 30 years: 80% (1).

But at the same time, there seems to be a endless list of promising solutions coming out of the lab. Renewable energies have managed the incredible feat of becoming cheaper than most other sources of electricity generation sources over the past few years (2), electric vehicle batteries are making incredible progress, smart meters can significantly improve the energy consumption within households… So how come the scientific community cannot come together to give governing authorities, industries and the general public a clear road plan to follow? Their colleagues over at the health department seemed to do a pretty good job repeating day-in, day-out: #washyourhands, #spreadthecurve, #staythefuckhome. Even if in hindsight some of the COVID-19 measures proved more effective than others, we reached these conclusions by first implementing them. It’s about time we do this leap of faith on the environmental side as well.

The biggest barrier within the academic community to implement this for sustainability is disappointingly simple: it seems impossible to reach a consensus on the road to follow. While an overwhelming majority agrees on the cause (took them long enough to do so), there are as many different solutions as there are research centres.

Part of this is due to the nature of the problem: for climate change, while the problem is a global phenomenon, the solutions have to be adapted to the local conditions. Inevitably, a researcher from Ghana will come to different conclusions than the one in Norway on how to best produce renewable energy.

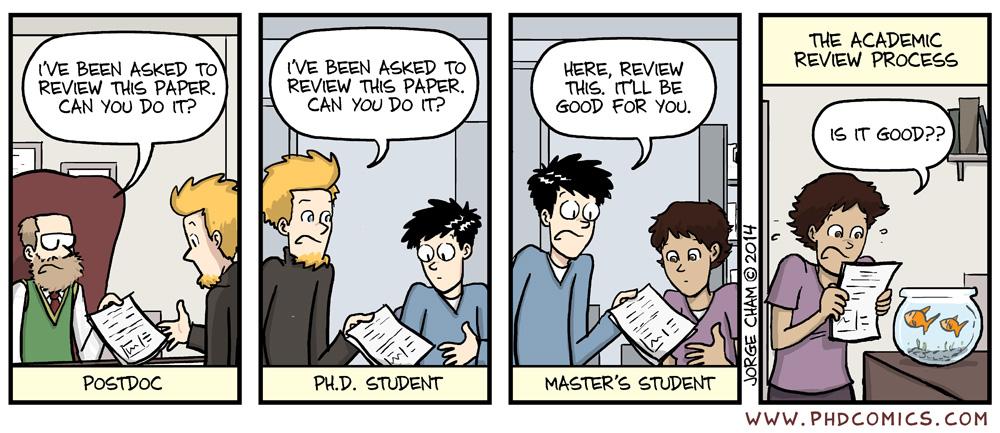

But another issue, which is the main point I wanted to get to (geez, finally!), is the way in which academics communicate their findings. What makes academic work trustworthy is not the brilliance of the researcher, nor the university he is affiliated to or the amount of money which has been dumped into the project. Instead, it relies on the fundamental concept of peer-reviewing: before any work is published, it must be reviewed by an external group of experts in the field to judge whether the work is of enough interest, of high enough quality and whether the applied methodology is rigorous enough. Of course, academics being humans, this process is not always impartial. However, it is the best we’ve got at the moment to avoid the “fake news” phenomenon infiltrating itself into academic circles. But this process, which is essential, often takes months before the final verdict falls. And so inevitably, the pace of “official” knowledge dissemination is relatively slow, despite all the work put in.

And once you’re through the holy gates of peer-reviewed articles, you still have to make it into the big wide world. While an academic’s work will not give THE answer to a question, it will give AN answer. A commonly used metric to assess whether this answer is worth listening to is the number of times an article / piece of work was cited. Indeed, any work in academia lies on the shoulders of others, and therefore you cite them in your own work. This is also why peer-reviewing is so important: if one brick in the pyramid is flawed, the whole structure crumbles.

So in a sense, academics have invented social media and have been giving each other “likes” long before Facebook was a thing :p. Except that you can’t just post whatever and whenever you want based on your mood. And this is why, in my opinion, the academic dialogue cannot keep up with the fast-paced news and medias nowadays. That 10-page bit of work paid with tears and sweat after 10 months of hard work will just get drowned in the constant stream of daily tweets. While I think it would be good for everyone to tweet a bit less and read a bit more, it is also up to the academics to adapt to their times and also get more involved in the public debate, communicating about their work in a more approachable way and include the general public more. This is not a call to transform publication journals into newfeeds, but an encouragement for academics to also disseminate their knowledge outside academic circles. If given the chance to understand it, many people might have their own word to say on the relevance of a particular work. The problem is, at the moment the public is only informed of this work through third-party sources or buzzfeeded summaries, which can dangerously deform initial results.

But this is where we hit another uncomfortable point for researchers (who already seem uncomfortable enough in the society they are asked to evolve in – just a bit of self-derision here 😉 ). For a scientist, a result is meaningless without its associated error. As you inevitably take certain assumptions to build up your experiments or models (I’m excluding the theoretical mathematician weirdos here), the results you get from your simulations, calculations and analyses will only be approximations to reality. And therefore it is fundamental to underline this uncertainty or deviation. In general, this leaves scientists to have very rational arguments, always counterweighting their results with the assumptions they’ve made.

Yet this cautious behaviour is again fundamentally at odds with the assertive tone of the self-proclaimed experts of the Internet. People nowadays want to hear facts (whether right or wrong), and elect people who “promise” to fulfill great electoral agendas. The rise in extremism seems to be more the death of moderated dialogue, leaving scientific (or rather, academic, let’s not forget the importance of the Humanities in the debate) dialogue very difficult. Yet when it comes to looking into the future, there’s no “fake” or “true” news: there’s just hypotheses, assumptions and a good dosis of uncertainties. In that case, consensus through informed dialogue is the only way forward (while also remembering to literally pick up the shovel once in a while).

In the end, what I’m trying to say, is that if we all agreed a bit more that there are a lot of things we don’t know, and won’t know until we try them out, then maybe this could help us make a step further and get going with implementing real solutions against climate change. But this requires more communication efforts from everyone, not least from the academic community’s side.